DETERMINERS OF THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE - Onyeji Nnaji

Determiners functions particularise the noun referent in

different ways: by establishing its reference as definite or indefinite, by

means of the articles (a book, the book, an actor, the actor), or relating the

entity to the context by means of the demonstratives this, that, these, those

(which are deictics or ‘pointing words’), signalling that the referent is near

or not near the speaker in space or time (this book, that occasion). The

possessives signal the person to whom the referent belongs (my book, the

Minister’s reasons) and are sometimes reinforced by own (my own book). Other

particularising words are the wh-words (which book? whatever reason) and the

distributives (each, every, all, either, neither). Quantifiers are also

included in the determiner function. Quantification may be exact (one, seven, a

hundred, the first, the next etc.

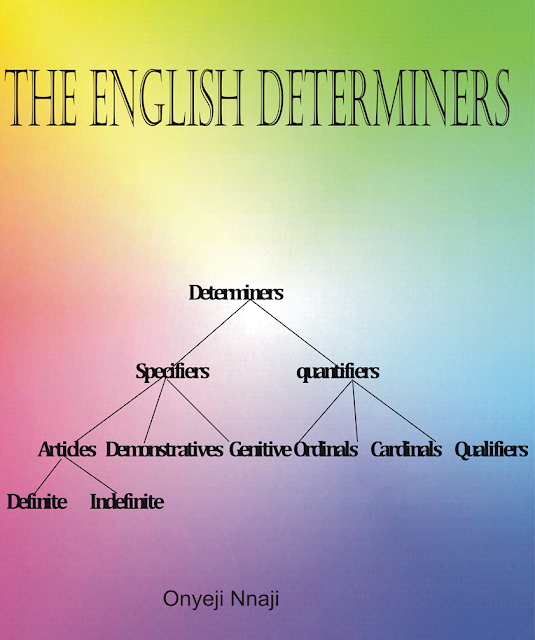

Determiners

are words that help to limit the meaning of nouns with respect to specification

(precision) and numbers. They usually appear before nouns or adjectives that

describe nouns. Example:

*

I need some money for shopping.

*

He would need many books for the

preparation.

The

italicised words above are determiners. Over hundred words are used to perform

the roles of determiners in various sentences and contexts. Many of these words

are drawn from pronouns, while others are from adjectives.

In the grouping of determiners, different

writer seem to toe different ways based on their definitions of determiner. For

instance, Swan defines determiners as words like a, the, this, my, some, every,

either, several, enough; they “come at the beginning of noun phrase, but they

are not adjectives” (ibid.: 147). This last clause is subject to skepticism.

Determiners are however taken as a part of the minor word class by some

linguists; they are taken from different parts of speech and assigned the

functions the play in identifying nouns. Many adjectives are wedded into

determines. Take the sentences below for example:

* Few

books were in the shelf at the library (few as a quantifier).

* Plenty

things await my arrival (plenty as a quantifier).

* New

girls are employed by the hotel management (new as a qualifier).

Also read: The Crosscategorial Features of Prepositions

In the argument of Swan (1996) as shown

above, few, plenty and new are in the above sentences

realized as adjectives; yet the argument that these various words, thought

adjectives but, used to identify the subjects of their content sentences is a

determiner individually is undisputable. In fact, all the qualifiers and

quantifiers that are not pronouns which are used to introduce nouns in

different sentences are adjectives, but determiners at the moment. Remember,

the subject is the head of the sentence and shares affinity with determiners

particularly. Therefore whatever word suitable to announce the subject at any

given time automatically becomes a determiner at the point; the class of the

word notwithstanding. Pertinent to this chapter are those determiners that are

closely aligned with sentence subjects. The

grouping below self-narratively explains determiners to any learner.

Many writers found it very

convenient to separate all, both and half as pre-determiners. I do not find

it convenient to group them thus. The reason is simple; virtually all

determiners could pre-determine their subjects while some selected numbers may

be marked Post modifiers. Of course, what we have carefully summarized into two

blocks (specifiers and quantifiers) above is broadened in different grammar

books as pre, central and post modifiers.

The difference is that the broad discussions by those grammar books were

intended to contain the modification roles of determiners across several

positions of nouns in sentences, not particularly the subject alone.

(1.1) Specifiers:

Specifiers are those determiners that are more or less marked for

specifications. They particularly do not indicate quantity like quantifiers.

Specific roles include denoting definiteness, indefiniteness, demonstrative,

and possessions etc. of the subjects they introduce. In The Structure of Modern English

Grammar, we discussed the

above specifiers roles under regular determiners and

pre-modifiers. Regular determiners are those determiners that are relatively

unchanging in their nature. As a part of specifiers, regular determiners are

marked specifically for specific numbers. They also are not intensified

further.

(1.1.1) The Article

Articles are the oldest of the determiners

taught in schools. It is the first aspect of determiners that students are

confronted with, earliest from the lower academic levels. Every child that had

passed through learning in nursery and primary schools is familiar with the

articles a, an and the. These are indefinite and definite

articles respectively.

(A) The Definite Article: The is termed definite article

because it is believed to specifically point at something definite. Definite

article, unlike the indefinite ones, does not specify the number of the

subjects it introduces. What is very pertinent to note is that “the” article speaks

of something that the audience is believed to have had information about

previously. Note: it is presumed; not that the audience must in all the cases

have prior information of the object in reference.

* The child is crying.

* The books are interesting.

* The men were obsequious.

The definite article is used in

two varying ways by speakers of the English language:

(1) The as a connotative

plural determiner: A closer observation

to the sentences above will prove to us that the definite article is used to

introduce subjects irrespective of their number. When the subject that the introduces is a proper noun in such a

way that such a subject has a connotative reference to a set or a collection of

species belonging to a common core, such a subject is realized as a plural

subject; and as such it agrees with plural verbs. Example:

* The Igbo are a distinct people

among Nigerians.

* The Yoruba are too subtle to

rely on.

* The Ngenes are people of war.

* The Onojas are men of high

standing.

* The government have passed a

decree.

Although it is convenient for the

subject (Government) to take singular verb, in is necessary to note that the

influence of article the is capable of compelling the same subject to take plural verb as

shown above. We must clarify our audience that this is one of the exceptional

conditions in the use of the definite article. This situation is not prominent

among users of the English language. Using the singular verb, has, in the above sentence is not wrong.

The reason it is cited here is to make users of the English grammar know that

it is not completely wrong should they hear or read such an expression. On the

other hand, it may be mildly defended to fall under Notional Concord. The

same idea also holds when management is

introduced by the. Example:

* The management have taken a

decision on the issue.

*

The management has taken decision on the issue.

(2) The as a deregulated

determiner: While in the first examples the is used for connotative reference, the

deregulated the does not follow any

constraint. It introduces any subject irrespective of its number. The

accompanying verbs this time agree with the subjects with respect to whatever

number the subject carries.

(B) The Indefinite Articles: While the

is marked definite, articles a and an are indefinite.

Indefinite articles are used to introduce subjects that are mainly common

nouns. The determiner of the suitable article to be used with any proper noun

is the orthography of such a word (s). Article a is used before those

subjects that begin with a consonant, while an is used to introduce subjects

beginning with vowel sounds.

* A woman

came looking for you.

* An Abam

warrior fought the Jukun singlehandedly.

* An orange was found on my

teacher’s table just now.

* An incubator saved the child

that was born prematurely.

* A man who eats outside lives

for the public.

(C) The Zero Article:

When a subject that is supposed to be preceded by a

determiner appears alone in a sentence and the absence of the supposed article

does not affect the meaning created by the sentence we say that zero article

has occurred. Put simpler, the absence of a marker which is grammatically

significant is called the ‘zero article’. ‘Zero’ doesn’t mean that an article

has been omitted, as may occur in most newspaper headlines, but is a category

in its own right.

* Orange is a good fruit.

* Book gives the highest

information.

* Name is an identity.

* War is politics carried out

by violent means.

* Television is a double

blessing.

The most frequent type of generic statement is the one

expressed by the zero articles with plural count subjects or subjects that are

common nouns.

* Ostriches are common in South

Africa.

* Courses offered in the

university are enormous.

Zero articles with plural count subjects may have generic or

indefinite reference according to the predication. See instance from the

sentences below:

* Frogs

have long hind legs (generic = all frogs).

* Animals

that live in captivity play with their food as if it were a living animal (indefinite = an indefinite number of food).

A subject comprising a mass noun with zero

articles can be considered generic whether or not it is modified:

*

Ghanaian coffee is said to be the best.

It is definite only when it is preceded by the.

Singular uncountable subjects expressing indefiniteness are used with the zero

articles (eg. Wine

is one of this country’s major exports). Indefinite plural

subjects are also used with the zero articles.

(1.1.2) Indicators

Our choice to separate demonstratives, non-assertive dual determiner and negative dual determiner from articles

is because it is discovered that, in the assessment of their relationship with

the subjects they introduce, they show more indication of numbers than articles. Again, while articles are conditioned by phonetic regulations, demonstratives, non-assertive dual

determiner and negative dual

determiner are not thus regulated. The regulation this latter group receive

is only prompted by the subject’s number. Their roles are generally to indicate

the subject being referred to.

(A) Demonstratives: Demonstratives are

determiners borrowed from demonstrative pronouns to indicate the numbers of the

subjects they introduce in sentences. They are pronouns used as adjectives to

modify nouns. As specifiers, they are marked for numbers. Examples:

* This generation is very inconsiderate (singular

subject).

*

That boy has been playing all day (singular subject).

*

These books were helpful to me during my exams (plural subjects).

*

Those goods have expired (plural subject).

Demonstratives particularise the subject

referent by indicating whether it is near (this, these) or not near (that,

those) to the speaker, in space or time or psychologically. They can refer to

both human and non-human entities in both singular and plural (this century,

these girls, that cat, those brakes). Like the demonstrative pronouns, the

determinatives are used in anaphoric, cataphoric and situational reference. An

anaphor refers to a word or phrase that refers to the activity in the past. The

demonstratives, this and that are used very often to make such a

reference. In the same way, these are

used to indicate anaphoric plural.

* This woman

is the thief who stole ice fish in the market.

* This meal

was Jane’s specialty.

* That food

was eaten already.

While anaphoric refers to a previous part of a discourse, cataphoric refers

to later part of a discourse. Anaphoric reference can be also indirect, which

requires some general knowledge. The cataphoric reference implies that

the identity of the reference will be established by what follows in the

discourse

* This is a

security announcement: Would those passengers who have left bags on their seats

please remove them?

The demonstratives this and these are also

used to introduce a new topic entity into the discourse. This use is particularly

common in anecdotes (stories) and jokes:

*

This man came up to me and said…, when I was walking along the street.

(B) Non-Assertive Dual Determiner: The term assertive refers to certainty in terms of exactness. For instance, the

sentence, Some students are sleeping in

the class while the teacher is teaching, is an assertive sentence because

the determiner, some, clearly

indicates that certain number of students are sleeping. It is not assertive

when the speaker says, anybody sleeping

in the class …. Determiners used for these senses are shown below:

Assertive Non-assertive

Determiners/pronouns some any

someone

anyone

somebody

anybody

something

anything

Non-assertive dual determiner uses the correlate, either, to show unspecific

reference about the subject of a sentence.

* Either

Jude took your wrist watch from this table or Diod did.

* Either mom

prepares this tasty soup or aunt Sabina.

There is no clear assertion in the above sentences about the certainty of the subject that performed the action involved. The non-assertive is dual because two correlates are involved in the subject’s role. When a correlate, either, is used alone the meaning about the missing subject would rather be implied, not stated.

(C) Negative Dual Determiner: In the

same way as has been explained above, dual determiner could be negative. In

this sense, the determiner tends to mean that none of the subjects in reference

is connected with the action performed in the sentence.

* Neither

side of the road is safe to wait a while.

* Neither

Jumi was there nor his wife.

* Neither go

to that market on time, else you will see nothing to buy.

(1.2) Quantifiers

A speaker may select a referent by referring

to its quantity, which may be exact (six students), non-exact (many brothers),

ordinal (the first friend), or partitive (three of my friends). Exact numerals:

these include the cardinal numerals one, two, three... twenty-one,

twenty-two... a hundred and five... one thousand, two hundred and ten, and so

on. These functions directly are determinatives. The ordinal numbers – first,

second, third, fourth, fifth . . . twenty-first . . . hundredth . . . hundred

and fifth and so on – specify the noun referent in terms of order. They

follow determinative subjects as in: the first time, a second attempt, every

fifth step, and in this respect are more like the semi-determinatives,

including the next, the last.

Quantifiers refer to determiners that show

quantity, group or mass. Quantifiers are mainly indefinite pronouns. Many

quantifiers accept the indefinite article “a” to express quantity. Only few

quantifiers are inflected for degree by accepting -er and -est morphemes while

introducing their respective subjects. Example:

* Fewer

students were in the class.

* The fewest

population met was not encouraging.

Indefinite quantifiers: some, any, no, (none).

Some specifies a quantity (with mass nouns) or a number above two (with count

nouns) as in some money, some time, some friends, some details. Other

quantifiers are used to express very small or very large amounts. The word, some, is pronounced in two ways, according to its functions. It has a weak form when

used non-selectively as an indefinite determiner, but it is strong when used as

a selective quantifier. Determiners sub-grouped as quantifiers are discussed

below.

(1.2.1) Numerals

Numerals simply mean numbers. It stands for

those determiners that introduce their subjects by specifying their numbers in

figure or in their order hierarchically (first, second…).

(A) Cardinal: These refer to determiners

of number or figures. Cardinal refers to such number as one, two, three … etc.

Cardinals always go with plural count nouns, except those which co-occur with

singular nouns. Example:

* Ten men

were in the hall.

* Two girls

went upstairs.

* One book

is with me.

In many instances, one is always replaced by

the indefinite articles “a” or “an”. In either ways, the proceeding noun is

usually single.

(B) Ordinal: This refers to first,

second, third… etc. Both can function pronominally and also as

pre-determiners/pre-modifiers. Some numerals such as hundred, thousand etc.

always have their pre-determiners (usually cardinals) deleted in some usage.

Meanwhile, in many of the cases, ordinals are pronominally preceded by

articles. Example: the tenth meeting etc.

Ordinals are relatively different; they

co-occur with singular nouns, except when such nouns connote a group. This

condition however is exceptional, otherwise, all ordinal co-occur with singular

nouns. Note also that it is characteristic of ordinal to introduce their

subjects with the help of either articles or possessives. Example:

* Today, the

fifteenth day of the month.

* The

eleventh boy is not in the class now.

* My first

friend has just travelled overseas.

* Thousands

of invitation cards were sent for her wedding announcement.

The plural indication of ordinals is

particularly peculiar to hundred, thousand, million etc. otherwise the ordinal

is preceded by a cardinal numeral. Cardinals and ordinals are qualifiers. We remarked

earlier that numerical determiners are sometimes substituted with partitives.

Partitives are words or phrases that function as determiners to indicate

quantity. Partitives have definite reference and represent subsets from already

selected sets. Details are discussed in (1.2.3) below.

(1.2.2) Digits

Ordinarily, digits refer to the set of

numbers or figures ranging from 0-9. The tendency to have mathematical figure

calculated on the bases of ten digits may be there. As determiner, digits refer

to those words (pronouns and adjectives) that are used to introduce subjects

that indicate mass number. They also introduce subject whose numbers are not

determinable.

(A) Multipliers: Another group of

predeterminers are multipliers. They have two types of use similarly to

predeterminers. Multiplier refers to the noun so determined with respect to its

quantity, e.g. twice the length, double the length, three times her salary,

etc. With the following determiner each

and every, or the indefinite article,

the multiplier refers to a measure,

e.g. once a day, four times every year, twice each game.

* Twice the

sun rotates daily.

* Once he

was given an offer to play for Liver Pool.

(B) The

general assertive determiners: Another

quantifier that requires attention is what Quirk and Greenbaum (1990) refer to

as the general assertive determiners. Some quantifiers are termed the general

assertion because, functioning as determiners, they really do not specify the

quantity of subjects (nouns) in reference. Quantifiers like some, many, few, little, much, plenty,

large, lots, bit, small, big, etc. can

be grouped together because of their wholesomeness. They show higher digits and

indicate quantity at a higher level.

* Some books

are not worthy of the library.

* Few students

were found on the streets around town.

* Many girls

wear nudity as a show of fashion.

The assertion found in the expressions above

depends on the fact that each of the quantifiers determines a general figure

that is greater that one. They indicate greater number than the more silent

determiners under the non-assertions

(C)The general non-assertive determiners: Unlike

the general assertive that indicates greater quantity without specification, the

non-assertive does not show any quantity; instead it gives indications of the

presence of its subject. Good examples of non-assertive determiners include any,

anything, anyone,

anybody etc.

* Any day is

okay by me.

* Anybody

can come to my office at will.

(D) The

quantitative determiners: Quantitative determiners are used to

determine quantity. In The structure of

Modern English Grammar, we grouped all the determiners under digit together

and separated them according to their degree of modifications. In that

distribution, what we have here as quantitative determiner was discussed as the

determiner that shows optimal range/rating as it is applied in

measurement. We have the distributions

as:

Enough is an optimal quantifier because it

indicates quantitative level, especially when it introduces non-count and mass

subjects/nouns.

*

Enough beans are served to the guests (normal, sizeable, sustainable quantity).

*

Enough books are in the shelf.

It is worthy of note to remind us that,

although enough is a determiner and a

pronoun, it can also be used in some sense to play the role of an adverb. This

happens when it ends a sentence.

(1.2.3) Universals

Universal determiners are so unique in the

sense that they are not presumably programmed to mark the numbers of their

subjects. They do not determine the number of their subjects; instead the

subjects determine their syntactic conditions. This type of determiners is mostly

used with singular count subjects (nouns). Particularly, the universal

determiners every and each, are peculiar for such singular

count subjects.

* Every

child is entitled to his right.

* Each

student takes a thousand from the money.

We can mark universal determiners for their

allocation roles. They allocate their subjects distributively. Again, the verbs

that follow the subjects introduced by universal determiners often agree in

singularity. The sentences above clarify these.

(A) Possessive: These include not just

the possessive determinatives such as my, his, her, its, our, your, their, but also the inflected (’s) genitive

form. The ’s determinative must be

understood in a broader sense than that of the traditional term ‘possessive’. All, both, half share a positive

characteristic, which means that they can stand before articles, demonstratives

and possessives.

* All the

students standing should return to the class.

* Both these

students were in the meeting.

*Half our

students are gone.

They can as well exist on their own without

occurring in front of determiners, such as every, each, some, any etc.; they

are quantifiers themselves. There are also rules for their particular use. All

is used with plural count and noncount subjects. This occurs when all is used as a monologues terminus

such that it determines a repressive ending.

* All books

are costly to buy.

* All music

are essential.

All can also

function as an individual each. In this condition, all rather acts distributively like every.

* All he

could do was to twist my hand.

* All the

money he has stolen, where is it.

Both is used

with plural count nouns, e.g. both the books, both books. Half is used with

singular and plural count and noncount nouns, e.g. half the book(s), half a

book. All/Both/Half of the students. All and both can also stand at the

adverbial position, e.g. The students both sat for the exam. Half, since it

may be a modifier, creates pairs of words or institutionalized compound, e.g.

half an hour, half a bottle of wine, etc.

Former and latter refer back to the

first and the second respectively of two entities already mentioned. They are

preceded by the definite article and can occur together with the ’s

possessive determiners.

* The

former’s was rejected.

* The

latter’s approved.

(B)

WH-Determiners:

WH-determiners, such as: which,

whose, whichever, whatever, whosoever, which are used as markers of relative

clauses. As determiner, they are indefinite relatives used to introduce

interrogatives.

* Which book

is more useful?

* What name

do you have?

* Whose book

are you reading?

*

Whichever is good?

Wh-determiners could also be used in

non-interrogative sentences. There are instances where wh-determiners are used

in assertive sentences to refer to something that had been spoken about.

* Whatever gain is profitable.

* Whatever gain is profitable.

*

Whosoever goes to school learns to be civil.

(C) The Negative Determiners: The last

of the quantifiers discussed here is the negative determiners. Negative

determiners are those quantifiers of no estimated extent. They are used to

introduce subjects that are indefinite in their references. Negative

determiners include no, nobody, no one, nothing, none, nobody etc.

* None will

attend the class, I assure you.

* Nothing is

happening anywhere.

* Nobody has

his cake and eats it.

.jpeg)

Thank you

ReplyDelete