ORIGIN AND HISTORY OF THE FULANI - Onyeji Nnaji

As a child, anytime we saw cows we told one another that

Fulani people were coming. As soon as that happened our mind became fixated. We

expected to see something different from the normal things obtainable in normal

societies. The Fulani, for instance, do not treat their children as nothing

different from slaves, savages and animals.

Their little ones were left to walk

barefooted in the hot sun, while their mothers comfortably carried fowls on

their backs. We knew them as a people who moved within cows, and a people

associated with the myth of turning into cows at night. We told ourselves about

the Fulani mystic powers and tried to compare them with the exchange of mystic

energy that dominated the challenges we saw during mystic festivals. The Fulani

mystic power were to us as the mere turning a rod into a snake by Moses in the

palace of Pharaoh. We had seen powers manifested beyond that. Yet we feared the

Fulani since they could magically turn to cows.

Beyond this, we saw among the Fulani a society where humans

were not given adequate care or concern. It was to us as though an average

Fulani child was left to his fate. And to attain the peak of their destiny in

life was the sole victory of assailing high as a herder. We looked at ourselves

and the nature of concern we received from our parents; turning to the helpless

Fulani children, as they seemed to us, we saw a world prepared for raising

people who would think no greater of others than mere animals that live in the

bush, pastured by a herder, who would be butchered without recourse to nature

instinct. Besides that, we saw beautifully slim-fitted young maidens that

walked with them. They carried

beautifully calved calabash on their heads freehandedly. “These ones would make

good wives”, we thought; only to bashfully receive from older brothers that, to

have a Fulani girl as a wife, one needs to engage in a fight of flogging rods.

Nothing about them read well to us and for which we could believe that a Fulani could possibly think of being educated in the western ways as we were undergoing then. Presently, I can see that there are highly enlightened Fulani; although their education does not remove those cannibalistic lifestyles imprint in their blood stream.

Nothing about them read well to us and for which we could believe that a Fulani could possibly think of being educated in the western ways as we were undergoing then. Presently, I can see that there are highly enlightened Fulani; although their education does not remove those cannibalistic lifestyles imprint in their blood stream.

People whom historians identify as Fulani entered

present-day Senegal from the north and east. It is certain that they were a

mixture of people from northern and sub-Saharan Africa. These pastoral peoples

tended to move in an eastern direction and spread over much of West Africa

after the tenth century. Their adoption of Islam increased

the Fulanis' feeling of cultural and religious superiority to surrounding

peoples, and that adoption became a major ethnic boundary marker. The Toroobe,

a branch of the Fulani, settled in towns and mixed with the ethnic groups

there. They quickly became noted as outstanding Islamic clerics, joining the

highest ranks of the exponents of Islam, along with Berbers and Arabs. The Town

Fulani (Fulbe Sirre) never lost touch with their Cattle Fulani relatives,

however, often investing in large herds themselves. Cattle remain a significant

symbolic repository of Fulani values.

ORIGIN OF THE FULANI

A search for the origin of the Fulani is not only futile; it

betrays a position toward ethnic identity that strikes many anthropologists as

profoundly wrong. Ethnic groups are political-action groups that exist, among

other reasons, to attain benefits for their members. Therefore, by definition,

their social organization, as well as cultural content, will change over time.

Moreover, ethnic groups, such as the Fulani, are always coming into, and going

out of existence. Rather than searching for the legendary eastern origin of the

Fulani, a more productive approach might be to focus on the meaning of Fulani

identity within concrete historical situations and analyze the factors that

shaped Fulani ethnicity and the manner in which the sect spread across nations.

Many people had tried tracing the historical origin of the Fulani

and failed because they sought to find ancestry for the sect among the Africans

of the west.

To find the origin of some African settlement in the west,

attentions needed to be given to other African settlements beyond the west. This

is because, many African nations could vividly speak of their migration from North

Africa than they could clearly speak of their emigration to the north. Take the

Akan, the Ganda, The Abaluya of Kenya (Kikuyu), the Zulu etc. for instance;

they could narrate their stories as Bantu who had travelled from unclear

destinations in the Northern part s of Africa than they could speak of their

original sources before their early settlement at the equatorial plane. The same

situation holds for the Fulani situation. Not even the Fulani could tell their

history. The reason is that they their life of hobo stole from them the memory

of having a source. No speck of this is contained in their oral tradition. The Fulani’s

oral tradition holds thus:

Geno, the Eternal Lord first created the cow. Then

he created the woman, only then the Pullo. He put the woman behind the cow. He

put the Pullo behind the woman. It is what the genesis of the drover says; it

is what makes the holy trinity of the pastor. Glory to the Creator of all

things - the chaos and light; the full egg and the great void! Frrom the drop

of milk, he extracted the universe; the teat, he brought out the word. Nomadic

speech: longest river of milk that multiplies the meanders between deserts and

forests to say and repeat the incredible adventure of Fulɓe.

According to Zain Agu in www.legit.ng, “Researchers cannot give an unambiguous

answer regarding the origin of Fulani tribe. There are several theories; it is

known that as a nomadic tribe they moved through many other cultures. The oral

histories of the tribe point to their origin in Egypt, but the language of

Fulani tribe seems to originate from Senegambian region.” The oral

history that traced the Fulani origin to Egypt was not completely wrong. The only

problem was that the writers claiming Egyptian origin for the Fulani lifted the

nomadic image painted in Black Genesis by Robert

Bauval and Thomas Brophy to show the lifestyle of the inhabitants of Nabta Playa

before its destruction. This same image was borrowed by Zain Agu to prove that

the Fulani had migrated from Egypt. But he was wrong.

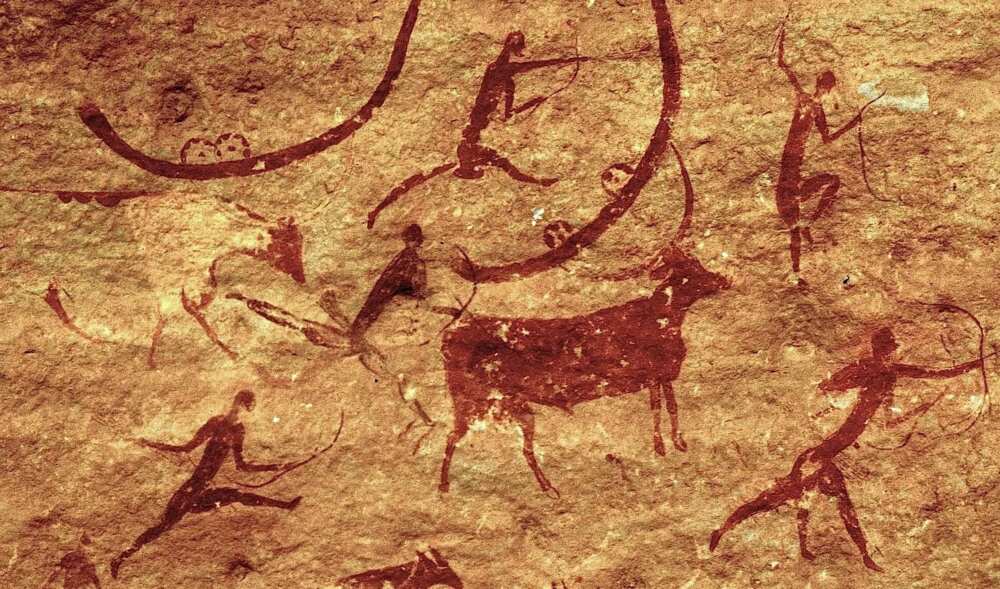

You will get this image on page 100 of the book, Black Genesis by Robert Bauval and Thomas Brophy.

The species of cow the Fulani are known with was particularly Egypt. The are different from the type of livestock found elsewhere in the Middle East or down here in West Africa. A clear evidence is found on the engraved image dating back to 4000 BCE and beyond. According to the observations made by Dr. Nieves Zedeño, Nabta Playa are remarkable as the home of this special species of cow. Found in Nabta Playa also was the cow emblem shown below.

This emblem was unearthed in the area where “wadi sacrifices” were conducted. It was concluded that these cattle burials and offerings appear to indicate the presence of a cattle cult. Radiocarbon dating placed these cow burials at around 5500 BCE, thus at least two thousand years before the emergence of the well-known cattle cults of ancient Egypt, such as those of the cow-faced goddess Hathor, the universally known goddess Isis, and the sky goddess.

Other proofs found at Nabta Playa are shown below.

The origin of the Fulani is traced beyond Egypt. Of course, basing one’s assertion on the similarities of Fulani and other parts of Africa, Egypt will be very far. The truth that cannot be overstated is the fact that the nomadic character that finally formed the base of what the Fulani hold as their totemic emblem was derived from Egypt. Aside that, a traditional Fulani person takes identical tribal features of the Ethiopians. The women below are good examples. Look at their faces; there is no difference between these women: traditional Habesha or an Eritrea women, Ethiopia, Eritrea and the Fulani girl at the right hand position, Ethiopian. They have the same tribal designs. By this, it invariably means that both people must have had contacts in the time past, even though there is no trace of Fulani in the Ethiopian history, past and present.

The species of cow the Fulani are known with was particularly Egypt. The are different from the type of livestock found elsewhere in the Middle East or down here in West Africa. A clear evidence is found on the engraved image dating back to 4000 BCE and beyond. According to the observations made by Dr. Nieves Zedeño, Nabta Playa are remarkable as the home of this special species of cow. Found in Nabta Playa also was the cow emblem shown below.

This emblem was unearthed in the area where “wadi sacrifices” were conducted. It was concluded that these cattle burials and offerings appear to indicate the presence of a cattle cult. Radiocarbon dating placed these cow burials at around 5500 BCE, thus at least two thousand years before the emergence of the well-known cattle cults of ancient Egypt, such as those of the cow-faced goddess Hathor, the universally known goddess Isis, and the sky goddess.

Other proofs found at Nabta Playa are shown below.

The origin of the Fulani is traced beyond Egypt. Of course, basing one’s assertion on the similarities of Fulani and other parts of Africa, Egypt will be very far. The truth that cannot be overstated is the fact that the nomadic character that finally formed the base of what the Fulani hold as their totemic emblem was derived from Egypt. Aside that, a traditional Fulani person takes identical tribal features of the Ethiopians. The women below are good examples. Look at their faces; there is no difference between these women: traditional Habesha or an Eritrea women, Ethiopia, Eritrea and the Fulani girl at the right hand position, Ethiopian. They have the same tribal designs. By this, it invariably means that both people must have had contacts in the time past, even though there is no trace of Fulani in the Ethiopian history, past and present.

The ancestral father of the Fulde, Fulbe, Fula, Fulani as

they may be called was King Hadad. King Hadad belonged to the strayed

descendants of Esau the elder son of Isaac. History made us to know that Esau

lived at Mount Seir where he built his city after his name, Edom.

The map of Edom on the plane of the Middle East alongside

her neighbours is shown below.

Hadad was the king of Elah, one of the eleven clans that

survived Esau. In the c11BC. Edom was

invaded by King David and his Joab led army. David destroyed many cities of the

Edomites. He destroyed Amalek a few days after Ziklag was invaded by the Amalekites. He burnt the land and destroyed it totally. Amalekites were the home of the descendants of Amalek who was the grandson of Esau's eldest son, Eliphaz (Gen. 36:16). This took place many years after King Saul defeated Edom and captured

Agag alive, in the same century. Hadad fled to Egypt and lived there till the year

David died, he returned. Meanwhile, Hadad had acquired cattle in Egypt. In the

days of Solomon, before the division of Israel and Judah, Hadad plot an attack

on Judah but he was not successful. He ganged up with the the remnants of the Medianites against the Israel. History

has it that both nations turned against each other in confusion and slew

themselves; Hadad ran away and Edom remained vassal hence as David had

subjected her. The final attempt by the Edomites took effect in the reign of Jehoshaphat, king of Judea (see II Chronicles 20). They were conquered by the same means; thereafter the remnants of mount syre (Edom) was ruled by delegates from Judah until Edom was shared

between Israel and Jordan. From then hence, Edom ceased to exist. This final act by Israel and Jordan fulfilled the scripture at Malachi 1:4 when God indeed says that he will destede the dwelling of Edomites continually until they cease to exist. Today, Fulani do not have any place called by their name. They can and will continue to live in recluse.

Some historians claimed that Hadad ran to Syre. But the Tanakh that discussed issues general

about the across Red sea history maintains that Hadad ran to Nubia and lived as

a nomad. He founded the Red Noba who was the first coloured Nubias. They also

were the earliest nomadic herders in the Nubia region in the late centuries before

our era. From the History of Wars adopted by the Ethiopian King, Ezana (330–356 AD) the situation of the spread of

the nomadic herders towards inner Africa was clear. The herders were at

continuous war with the Black Nobas. At the time when this migration downward began,

Ezana noted that it was rather “Hasa

and Barya, and the Black Noba” who “ waged war on the Red Noba.” Ezana fought

in favour of the Red Noba.

I took the field against the Noba when the people of Noba

revolted and did violence to the Mangurto; Hasa and Barya, and the Black Noba

waged war on the Red Noba. I fought on the Takkaze [Atbara] at the ford of

Kemalke. They fled, and I pursued the fugitives twenty-three days slaying them

and capturing others and taking plunder; I burnt their towns, and seized their

corn and their bronze and the dried meat and the images in their temples and

destroyed the stocks of corn and cotton; and the enemy plunged into the river

Seda [Blue Nile].

It

was about this time (340s – 350 AD) that the Fulani began to advance downward

towards West Africa.

For the fully nomadic Fulani, the practice of transhumance,

the seasonal movement in search of water, strongly influences settlement

patterns. The basic settlement, consisting of a man and his dependents, is

called a wuru. It is social but ephemeral, given that many such

settlements have no women and serve simply as shelters for the nomads who tend

the herds.

There are, in fact, a number of settlement patterns among

Fulani. In the late twentieth century there has been an increasing trend toward

livestock production and sedentary settlement, but Fulani settlement types

still range from traditional nomadism to variations on sedentarism. As the

modern nation-state restricts the range of nomadism, the Fulani have adapted

ever increasingly complex ways to move herds among their related families: the

families may reside in stable communities, but the herds move according to the

availability of water. Over the last few centuries, the majority of Fulani have

become sedentary.

Those Fulani who remain nomadic or seminomadic have two

major types of settlements: dry-season and wet-season camps. The dry season lasts

from about November to March, the wet season from about March to the end of

October. Households are patrilocal and range in size from one nuclear family to

more than one hundred people. The administrative structure, however, crosscuts

patrilinies and is territorial. Families tend to remain in wet-season camp

while sending younger males—or, increasingly, hiring non-Fulani herders—to

accompany the cattle to dry-season camps.

ATTAINING A STATE OF EMPIRE

The Fulani movement in West Africa tended to follow a set

pattern. Their first movement into an area tended to be peaceful. Local

officials gave them land grants. Their dairy products, including fertilizer,

were highly prized. The number of converts to Islam increased over time. With

that increase, Fulani resentment at being ruled by pagans, or imperfect

Muslims, increased.

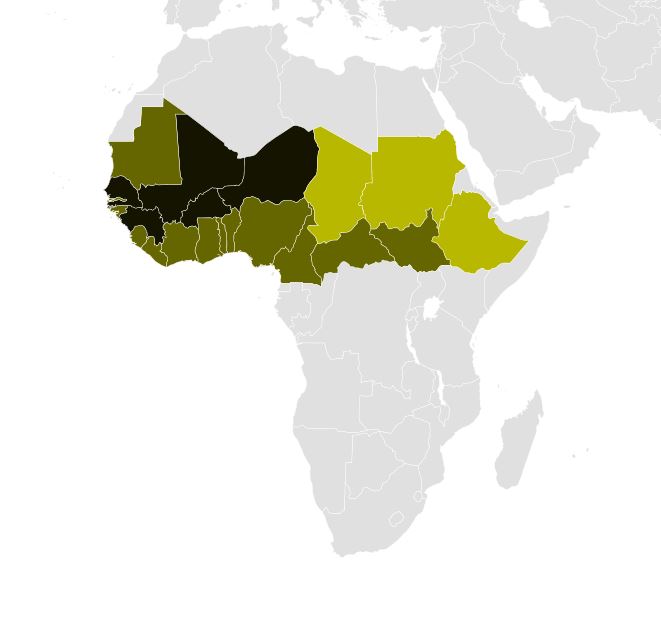

The attempts to suddenly emerge and rise as an empire in the Western part of Africa stemmed from the desire to dominate. This officially became the plan of the Fulbe beginning with their encounter with the Islamic religion. seeking to redefine their inferior state and degraded standard of life, they found the religion relevant towards achieving their intention. first, their conquering and overtaking of Fouta Djillon highland in the Central Guinea. Fouta Djillon formed the first part of Africa where ethnic cleansing was first practised. Ethnic cleansing is the Fulani strategic process of overpowering the inhabitants, wiping the owners and replacing them with vast Fulani numbers. The attempt worked out well in Fouta Djillon as the Guineas did not pose much restraint. After de-settling the indigenous and replacing them with the crowded Fulbe that flooded in from the Nubia (present day Sudan). From there they advanced through south into the northernmost reaches of Sierra Leone; the Futa Tooro savannah grasslands of Senegal and southern Mauritania; the Macina inland Niger river delta system around Central Mali; and especially in the regions around Mopti and the Nioro Du Sahel in the Kayes region; the Borgu settlements of Benin, Togo and West-Central Nigeria; the northern parts of Burkina Faso in the Sahel region's provinces of Seno, Wadalan, and Soum; and the areas occupied by the Sokoto Caliphate

The Maasina Emirate, also called Diina ("religion"

in Fulfulde, with Arabic origins), was established by the Fulbe jihad led by

Sheeku Aamadu in 1818. The origins of the Maasina Emirate in the Inner Delta of

the Niger are also found in rebellion, this time against the Bambara/Bamana

Kingdom of Segou,

a political power that controlled the region from outside. This jihad was

inspired by events in northern Nigeria where an important scholar of the time,

Usman Dan Fodio, established an Islamic empire with Sokoto as its capital.

For some time, groups of Fulbe had been

dominant in parts of the delta, thereby creating a complex hierarchy dating

back through several waves of conquest. However, due to internecine warfare

they were never able to organize a countervailing force against the Bamana

Kingdom. In 1818, an Islamic cleric named Aamadu Hammadi Buubu united the Fulbe

under the banner of Islam and fought a victorious battle against the Bamana and

their allies. He subsequently established his rule in the Inland Delta and the

adjacent dry lands east and west of the delta.

This state appears to have had tight control

over its core area, as evidenced by the fact that its political and economic

organization is still manifested today in the organization of agricultural

production in the Inland Delta. Despite its power and omnipresence, the

hegemony of the emirate was constantly threatened. During the reign of Aamadu

Aamadu, the grandson of Sheeku Aamadu, internal contradictions weakened the

emirate until it became easy prey for the forces of the Futanke, which

subsequently overthrew the Maasina Emirate, in 1862. Fodio had trained army for his intended Jihad which was suddenly usurped by the Middle Beltans before the approach of the colonial masters to that region.

The situation in Nigeria was somewhat different from that elsewhere in West Africa in that the Fulani entered an area more settled and developed than that in other West African areas. At the time of their arrival, in the early fifteenth century, many Fulani settled as clerics in Hausa city-states such as Kano, Katsina, and Zaria. Others settled among the local peoples during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. By the seventeenth century, the Hausa states had begun to gain their independence from various foreign rulers, with Gobir becoming the predominant Hausa state.

The Jihad intention of the Ibn Fodio led army did not relent in their mutiny of the Nigerian area after they had conquered the entire northern Part. They did advanced towards the southern part. The wall of difficult passage formed by the Nigerians in the Belt Middle posed difficulties to the Fodio adventure. The Benue/Tivs stood their ground and refused to be captured. They fought the Fulani Army for months until, unfortunately for the Middle Beltans, the colonial masters suddenly arrived. About that time, in the Midd 1800s, the British colonialists had already defeated the Western Yoruba waterfront and had moved down to the southern part. With the eastern Igbo overtaken by the colonial masters, the middle belt region was left a stone thrown distance to be captured. Therefore, they advanced towards the northern part.

At Benue there was a clash of interest as against the relentless warriors of the belt who was not prepared to give up the fight against the Fulani Jihadists. The colonialists were stupefied by the level of the already made army with weapons fighting themselves. They had to intervene by mediating amidst the fighting nations. To achieve this they had to think business with the people. The Middle Beltans needed to remain on their land and live their lives the way customary to their tradition. Turning to the Fulani Jihadist, it was discovered that the Fulani had the same intention as that of the colonial masters. At this point they entered into agreement. The British colonialists made a promise to return the territory to the Fulani after their colonial business.. This agreement ended the war and the Fulani retired to the Northern part of Nigeria which had already been conquered.

This agreement was the sole reason why a Fulani had to take over power from the colonial masters. The later mutiny in the Benue valley, particularly the event of the 1st January,2017 that led to the death of over seventy Benue citizens was born from the long-held acrimony over the failed jihad attempt.

This and many more mayhem are found deserving by the Fulani who saw it as retaliations for the Benue's gallant attempts to usurp the Jihad intention targeted at Islamisng the entire Nigeria.

The urban culture of the Hausa was attractive to many

Fulani. These Town or Settled Fulani became clerics, teachers, settlers, and

judges—and in many other ways filled elite positions within the Hausa states.

Soon they adopted the Hausa language, many forgetting their own Fulfulde

language. Although Hausa customs exerted an influence on the Town Fulani, they

did not lose touch with the Cattle or Bush Fulani.

These ties proved useful when their strict adherence to

Islamic learning and practice led them to join the jihads raging across West

Africa. They tied their grievances to those of their pastoral relatives. The

Cattle Fulani resented what they considered to be an unfair cattle tax, one

levied by imperfect Muslims. Under the leadership of the outstanding Fulani

Islamic cleric, Shehu Usman dan Fodio, the Fulani launched a jihad in 1804. By

1810, almost all the Hausa states had been defeated.

Although many Hausa—such as Yakubu in Bauchi—joined dan

Fodio after victory was achieved, the Fulani in Hausaland turned their

religious conquest into an ethnic triumph. Those in Adamawa, for instance, were

inspired by dan Fodio's example to revolt against the kingdom of Mandara. The

leader was Modibo Adamu, after whom the area is now named. His capital is the

city of Yola. After their victories, the Fulani generally eased their Hausa

collaborators from positions of power and forged alliances with fellow Fulani.

.jpeg)

Comments

Post a Comment